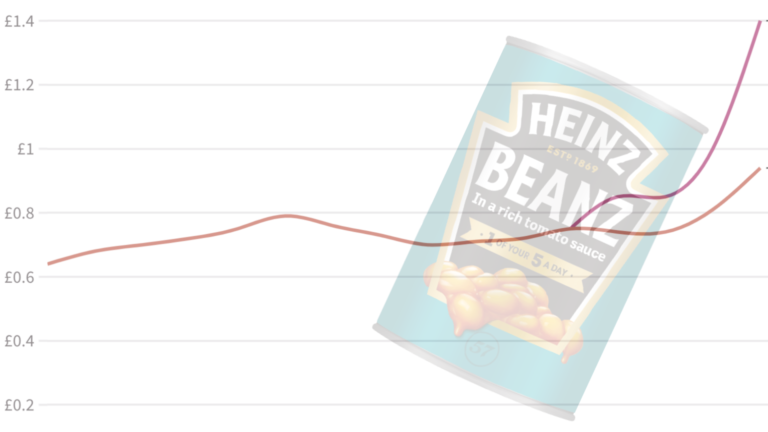

Ah, 2021 to 2022. When I would walk through the store, look at my favourite brand of olive oil, and watch its price go up, and up, and up…

The grocery cost of living crisis has abated a bit, with the latest measure of inflation at 3.8%, down from its dizzying 9.6% (CPIH) in October 2021.1Well. We say dizzying. However, the rest of the world says “welcome to the party”. A family member of mine who works in finance in Sub-Saharan Africa called the cost of living crisis “The West’s Baby Inflation”. According to the IMF, In 2021, one country had inflation above 1,000% (you can guess which one), two between 100% and 1000%, and nine between 20% and 100%. Not all of them were war torn, or making bad policy decisions Sometimes it’s just really really bad luck. Which some of our cost-of-living crisis was.

But September 2021 to September 2022 was a gruesome period to people’s household finances, and restaurant costs.

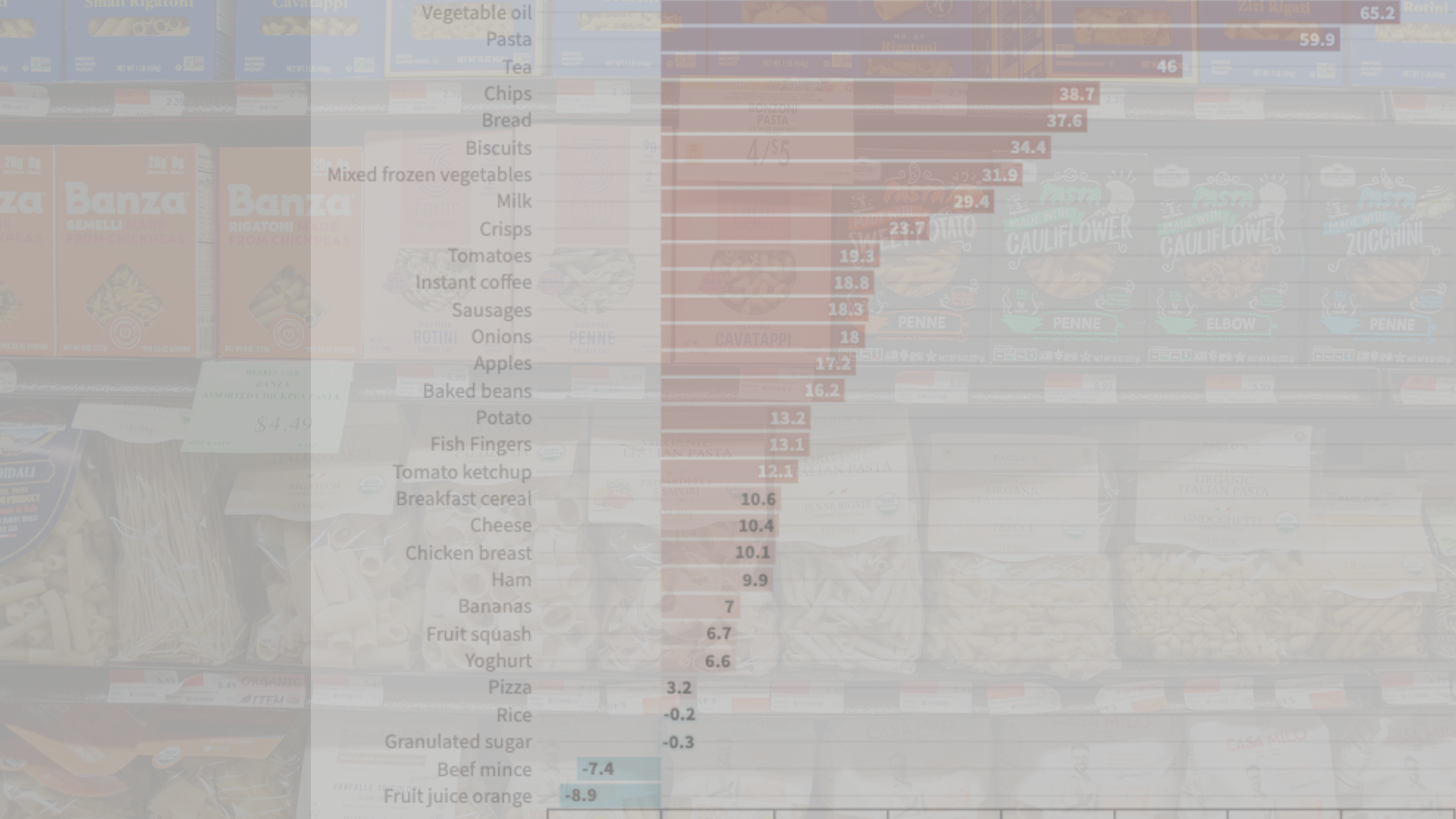

The ONS, took a bit of a detour from its usual inflation reporting, to web scrape the average price of the cheapest goods across multiple online supermarket retailers, between September 2021 and September 2022, and came up with the above dataset.2https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/articles/trackingthelowestcostgroceryitemsukexperimentalanalysis/april2021toseptember2022

They admit it’s an experimental methodology, and it was done on a one-off basis.3I didn’t spend my entire time reading the methodology, or look into their new inflation methodology much, but one speculates that this exercise was a bit of research creativity while they were updating their basket-of-goods for measuring inflation in 2023.

At the time I remember thinking “damn, inflation is a beast. Everything is going up.”

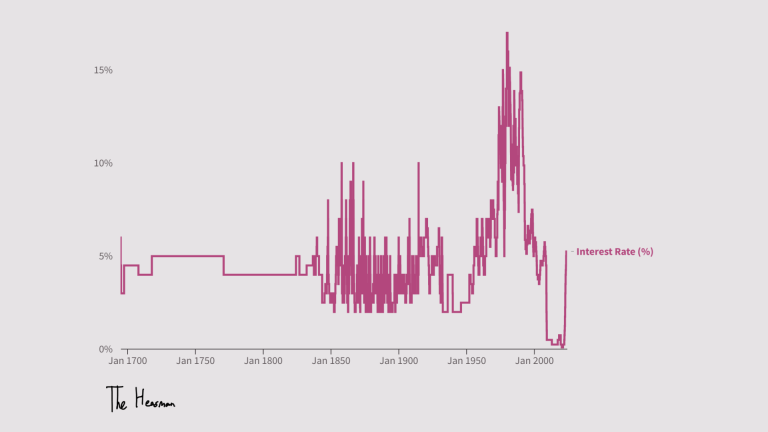

But not all of this was down to your usual run-of-the-mill inflation. Prices weren’t going up because people were flush with cash.4Your reminder that one obscure cause of inflation can be “the velocity of money related to the supply of money”. This tends to be what interest rates try to control. Basically, if everyone starts spending all their cash at once, there will be much more demand than supply. Everyone wants a new bed. The people making beds can’t just grow their business overnight. So prices will rise. This is known as a demand shock. If there is a lot of money swirling around (say due to generous fiscal policies), then wages will rise, as labour negotiates for more pay to account for rising prices. This leads to a wage-price spiral. Wages go up to pay for rising prices. Prices continue to rise because of demand. Runaway inflation begins. See Argentina, Venezuela, (and Türkiye between 2020 and 2023). Interest rates are a tool to keep this runaway inflation in check. Rising interest rates means that people are incentivised to save their money instead of spending it. However, inflation sometimes isn’t caused by a demand shock. As vegetable oil and pasta weren’t.

Let’s look at the two top items that saw price surges: vegetable oil and pasta.

A Drought in Canada

In the summer of 2021, Canada faced a sudden shift in weather. Temperatures reached record highs of nearly 50 degrees, and rain just decided it didn’t want to fall.

43% of Canada was classified as what the Canada Agricultural Office calls in typical Canadian understated fashion “Abnormally Dry”, or “Moderate to Exceptional Drought”[5].5https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2021/aac-aafc/A27-39-2021-8-eng.pdf

And a whopping 79% of Canada’s agricultural land was classified between “Abnormally Dry” to “Exceptional Drought”. Four out of five acres of Canada’s agricultural land was too dry to grow things.

Canada is the biggest producer of two things in global supply chains: durum and rapeseed oil.

Durum is used in pasta, and after the drought, prices of Durum rose by 90%. A food industry expert predicted that a packet of spaghetti would rise by 50%.[6]6https://www.theguardian.com/food/2021/sep/09/penne-in-your-pocket-uk-shoppers-could-pay-up-to-50-more-for-pasta

I hope that expert had access to trading of commodity futures because he would have made a pretty penny off that prediction. Prices ended up rising, as we can see, by 60%. Remember – this was the ONS tracking the cheapest brand of the product.

Now for rapeseed oil? Well.

There’s a bit more to that story.

Tomorrow I’ll write about why the price of vegetable oil skyrocketed. It isn’t as simple as “rapeseed oil went up, so vegetable oil went up”.

But what this illustrates is that the cost of living crisis wasn’t just because of increased spending power, and Trussonomics (though that really didn’t help).

Vegetable oil and pasta prices rose because of supply shocks, not demand shocks.

They rose because supply suddenly became constrained, and thus prices rose. While a decent amount of the cost-of-living was a demand shock, where there was a global post-pandemic spending splurge, and Brexit meant importing was logistically harder, so prices went up.

But anyway. Enough of the home economics lesson.

Time to go back to your LinkedIn feed and read yet another “this-really-should-be-for-instagram-not-linkedin-but-im-going-to-read-it-and-click-like-anyway”.

And I’ll see you tomorrow to explain why the cost of chips and garden salads from your favourite pub went up.